Jewish Airmen in the Great War

I have been involved with WWII a great deal in all of my various reincarnations; as an actor, voice over artist, script writer, video editor and translator. I lived in Germany for 20 years and was surrounded by links to that past. Horror, humour, courage, nobility. Now for the first time, I am delving into the Great War, brought there by the German language, approaching it as a translator.

The book I am translating is short; “Jewish Airmen in the Great War”. I wish it were longer. Airmen are glamourous to us and their stories grip me. On occasion I feel tears rise as I translate. That happens. I have mentioned before that translation can make me feel like a friend to those whose spirits emanate from the pages. And when those spirits belonged to young men, full of hope and enthusiasm, whose lives were curtailed so brutally, then I prove that I am “built close to the water”, as the Germans say. In other words, tears are never far away. My Celtic blood. Say no more.

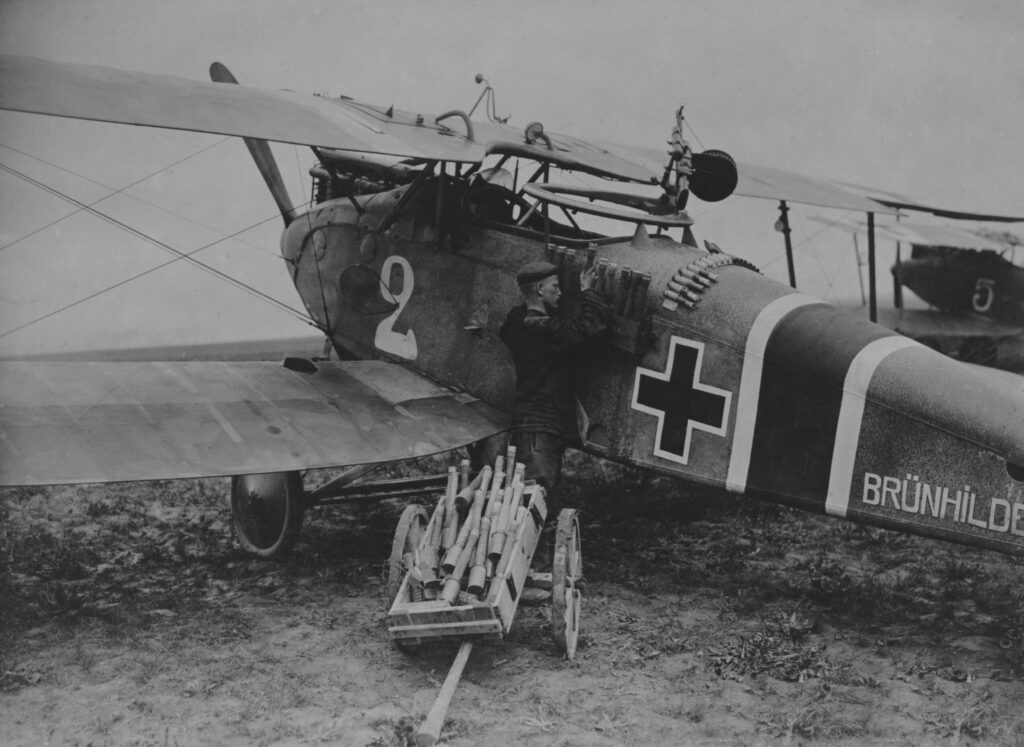

I am referring to airmen here. A rare breed in the Great War. German Jewish airmen, an amalgam which makes the narrative all the more poignant. I am translating a series of books dealing with the German Jewish experience in the 1914-18 conflict. Before I began, I knew as little about this experience as the next man so my interest in history was kindled in a new way, heightened by the knowledge of what was to come less than 20 years later. Those writing and written about, had not one iota of an idea about what was to come. Their perspective on the future makes for fascinating reading.

The book itself is unique. There were relatively few airmen and just a handful of Jewish aviators. Their backgrounds have been traced as well as could be by the author, and the men given their deserved public recognition. Through the airmen’s letters, and it is this method of carrying the narration forward which makes the tears well up, I can fly with them and share in their aviator joy over the front lines on the Western Front. I must linger upon the words of sorrow for longer than other readers would do. I must choose carefully how to accurately express degrees of sorrow and capture a sentiment without exaggeration or diminution, for the same word used by a different person in a different relationship can imply a different intensity of sentiment. And lingering also brings personal thoughts. Thoughts of myself at the same age. My own son. Of dedication to a cause. The easy exploitation of young, excited boys and men. Waste. Courage. The danger of powerful egos.

It is a strange sensation to be moved by the deaths of soldiers who were the enemies of those fighting for England and America. Killed by an English bullet or an American or French one. Yet there it is. And one takes refuge in hackneyed phrases for what else is there? War is madness. We only want peace. It is not you my brother it is the system that brings us into conflict. And so on.

This work has been a humbling experience. It is a privilege to help bring these texts to a wider audience. Being a translator brings rich rewards when words are so powerful. I would not not miss a single tear.

“Listen, in the air

our thoughtful spirits are circling

ever higher, ever faster

the engines and propellors drumming and whirling . . .”

The text goes on to say:

“The man who wrote this was taken away from rich poetic creativity by death on the battlefield near Soissons on the 8th February 1915, and his grateful homeland created a memorial to him on the eternally-cresting Baltic Sea, to the young Walter Henmann.”

(I wonder, of course, if this was a relative of Tim Henman the British tennis player? A long shot, so to speak, but I would find that very satisfying.)

I look forward to the next text, the next riddle of language. The new people and places, the learning in “overdrive” as translator Salvador Virgen described it; always learning; that is a valuable note for my life.